Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Quick Summary

#TLDR

An expensive X-ray scanner stopped working when the company that made it went bankrupt and the built-in computer failed. The software only worked with the original motherboard. I analyzed the program and modified it so it would run on a normal $200 computer, bringing the machine back to life.

The $15,000 X-Ray Scanner

We’ve all seen them at airports: the conveyor belt X-Ray scanners that check your luggage. They are massive, complex pieces of engineering involving lead shielding, high-voltage generators, and detector arrays. They cost upwards of $15,000.

Recently, one of these units reached its “End of Life” in a warehouse I was consulting for. The X-Ray mechanism was pristine, but the internal computer controlling it had died completely.

The catch? The manufacturer had gone bankrupt. There was no support line to call, no spare parts inventory, and no authorized technicians.

We had a simple plan: Swap out the dead, proprietary industrial PC for a standard $200 desktop. However, when we booted up the software on the new PC, it refused to function. The application launched, but the configuration files wouldn’t load. The machine was effectively bricked.

—> It’s debugging time!

The Diagnosis: Encryption & Hardware Locks

#Diagnosis

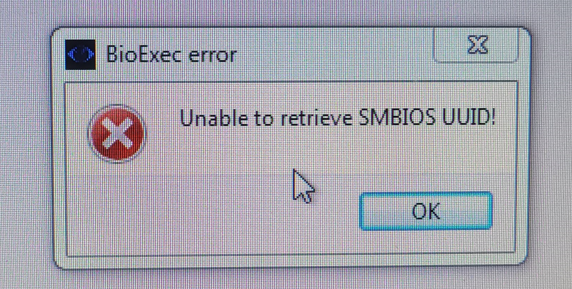

I started digging into the error logs. The application was failing to load the main configuration file (which controls the X-Ray generator voltages and sensor calibration).

Loading the config file, it is obviously encrypted. After some initial poking around, I realized the decryption key wasn’t hardcoded; it was being generated dynamically based on the hardware UUID of the motherboard.

Because we swapped the motherboard, the UUID changed.

Therefore, the software generated the wrong decryption key, failed to read the config, and locked us out.

I had two choices:

- Crack the encryption algorithm (math-heavy and time-consuming).

- Trick the software into thinking it was still running on the old computer.

I chose option 2. Because sometimes the smartest solution isn’t the hardest one xD.

Static Analysis with IDA Pro

#static_analysis

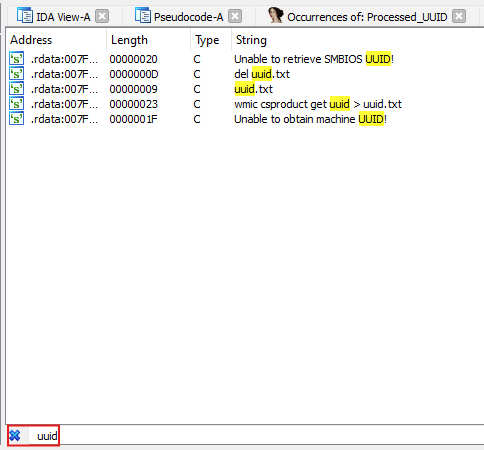

I pulled the main executable off the drive and loaded it into IDA Pro (Interactive Disassembler). My goal was to find how the software was fetching the UUID.

I started by looking at the Strings view. I searched for terms like “UUID”, “Serial”, “BIOS”, and “GetSystemInfo”.

Buried in the strings list, I found a reference to a filename: uuid.txt.

This was suspicious. Why would a professional piece of firmware need a text file named uuid.txt?

Dynamic Analysis: Catching the Ghost File

#dynamic_analysis

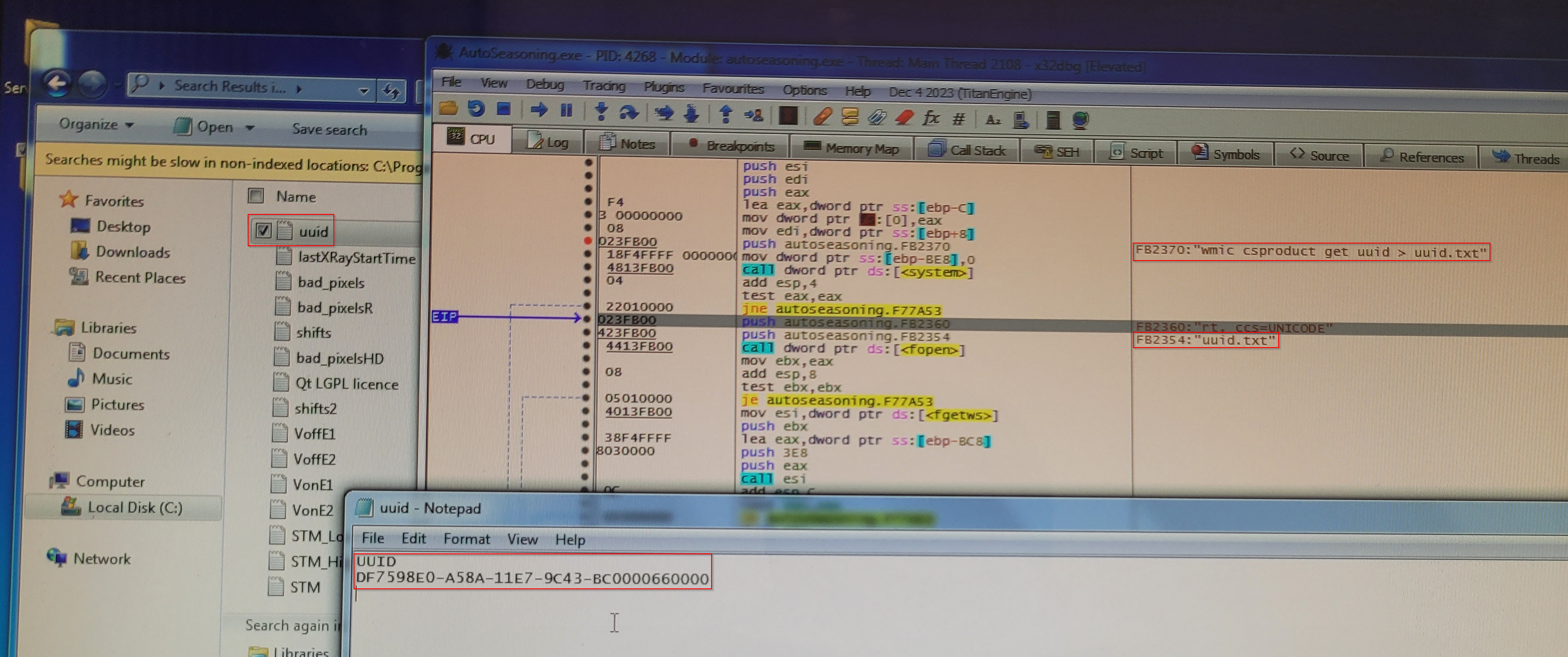

To understand how this file was used, I ran the software while monitoring the file system.

The behavior was incredibly inefficient, which was lucky for me. Here is the logic flow the software used on startup:

-

Query the Windows API for the machine’s UUID.

-

Write that UUID into a file named

uuid.txtin the current software folder. -

Read the content of

uuid.txtback into memory. -

Delete

uuid.txt. -

Use the string from the file to derive the encryption key.

The file existed for only a fraction of a second. The software wasn’t just checking the hardware; it was using the file system as a scratchpad.

I noted down that UUID, which is the UUID of the original x-ray embedded computer, and moved on to the patching phase.

The Patch

The Attempted Fix (and why it failed)

#failed_patch

My first thought was simple: Race the software. I tried to create a read-only uuid.txt in that application folder containing the correct UUID (the one that matched the encryption key).

—> It failed. The software forced a delete/overwrite operation. Because the file was locked or read-only, the software threw an exception and crashed. I couldn’t simply replace the file because the software insisted on generating it fresh every time.

The Solution: The Temporary Binary Patch

#successful_patch

Why temporary? Because patching the system directly without getting paid is a huge risk.

I needed a solution that would work right now for the demonstration, but fail if they tried to use it after a reboot.

That’s why I let Windows ASLR do the work for me.

If I couldn’t change the file system behavior, I had to change the software’s brain.

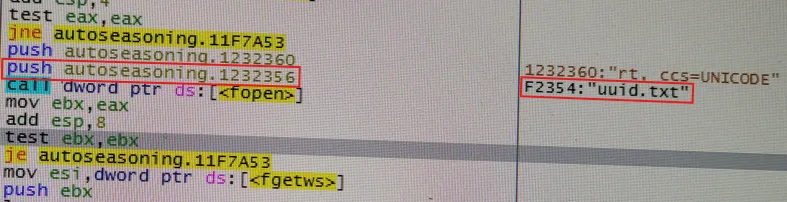

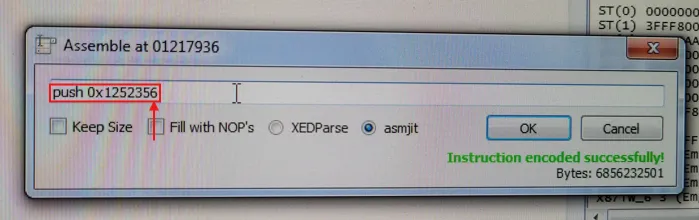

I went back to IDA Pro. I located the subroutine responsible for reading the file. It pointed to a data offset containing the string uuid.txt.

The Idea: I cannot modify the Windows UUID easily, but I can tell the software to look somewhere else.

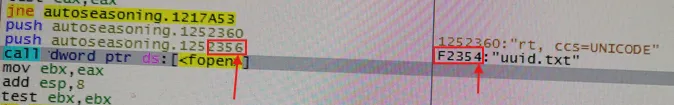

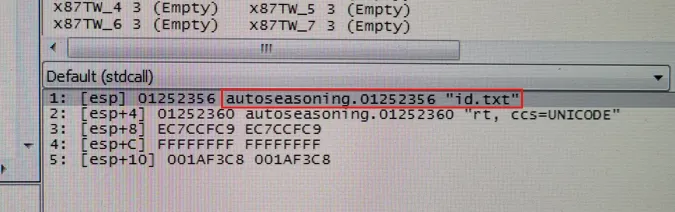

I made a hard-coded offset moving the address from 0x1252354 to 0x1252356, this way it read id.txt instead of uuid.txt.

The contents of id.txt would obviously be the UUID of the original embedded machine for the encryption logic to work as expected.

Well, you might ask: why not just follow the memory dump and edit the bytes of uuid.txt to id.txt directly in memory?

This is where Windows ASLR comes into play. I was deliberately relying on ASLR to break my own patch. Since the addresses change on every reboot, the patch wouldn’t survive a restart.

That way, if there were any issues with payment, the patch would simply stop working xD

I essentially used ASLR to my advantage to create a demo version of the patch.

By changing the target filename to id.txt, I broke the link between the generator and the reader.

-

The software queries Windows and writes the real UUID to uuid.txt.

-

The Patch: The software then tries to READ from id.txt (due to my hex edit).

-

The software uses the content of id.txt for the encryption logic.

The Result

I created a file named id.txt in the program’s directory. Inside, I pasted the UUID required to decrypt the configuration file.

I double-clicked the patched executable.

-

Status: Loading Config…

-

Status: Decryption Successful.

-

Status: System Ready.

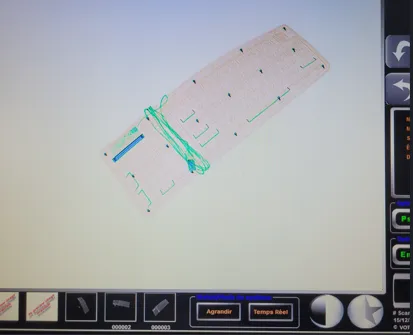

The conveyor belt hummed to life. The X-Ray generator warmed up. The $15,000 scanner was back in business, running perfectly on a $200 commodity PC.

I did put my keyboard in there to test if everything works fine, and it did!

Conclusion

This experience highlights a major issue in industrial tech. When companies go bankrupt, perfectly functional hardware often becomes e-waste due to arbitrary software locks.

By shifting a few bytes in a hex editor, we bypassed the hardware enforcement, allowing us to maintain the “Right to Repair” and keeping massive industrial equipment from going straight to waste.